Four Critical Aspects to Consider Before Afforestation or Reforestation to Combat Climate Change

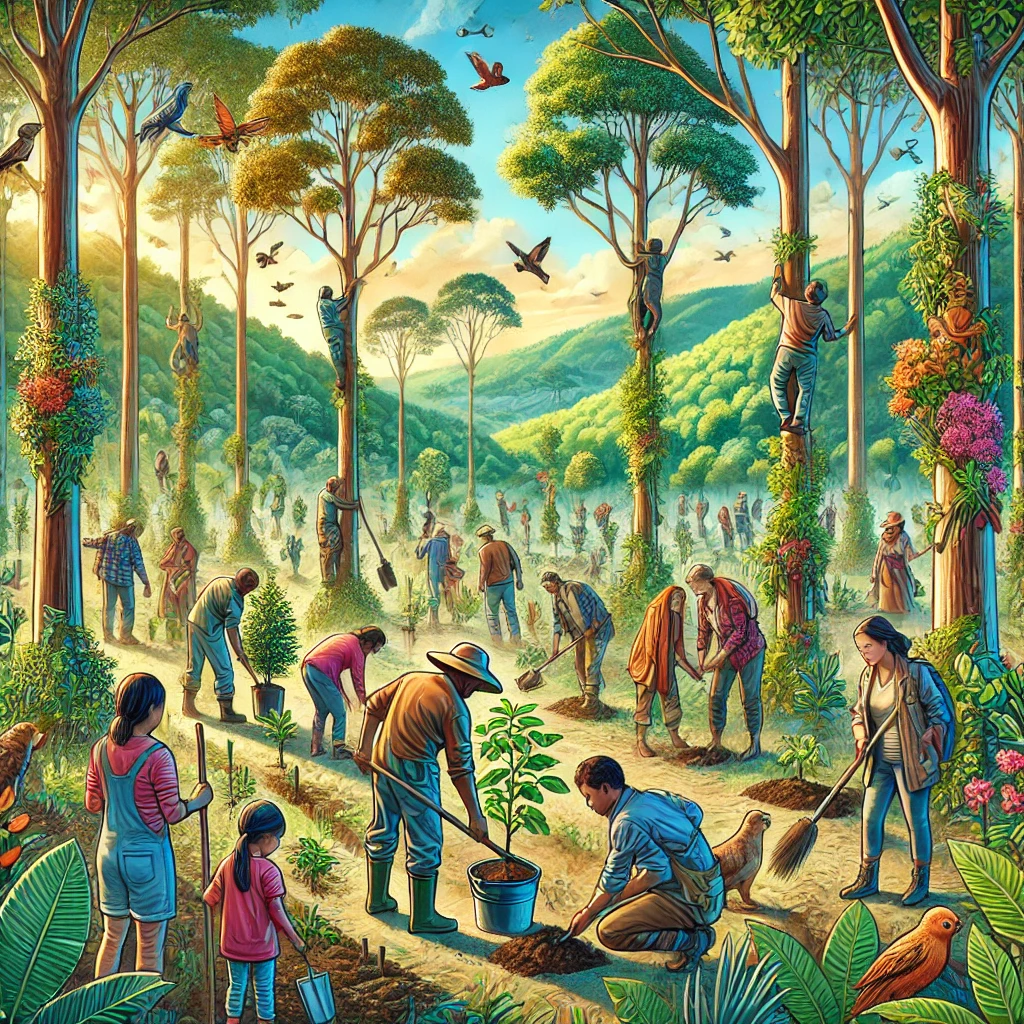

Before planting your first sapling, pause—afforestation and reforestation aren’t just about digging holes and dropping seeds. Get these four critical foundations right—from choosing the right species and testing the soil, to evaluating water needs and ensuring long-term stewardship—or risk planting failure, wasted resources, and even ecological harm

In the battle against climate change, afforestation and reforestation are being touted as two key strategies to reclaim a semblance of balance in our ecosystem. The science is intuitive—trees, through photosynthesis, absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, significantly reducing atmospheric carbon levels. A single mature tree, as the Arbor Day Foundation states, can absorb over 21.7 kilograms of carbon dioxide annually. Yet, while tree planting seems a simple solution, the reality is layered with complexity. Effective efforts must be deliberate, guided by science, and rooted in ecological integrity.

Here are four critical aspects to consider:

- Ecosystems: Understanding the Natural Blueprint

The world’s ecosystems—defined meticulously in frameworks like the IUCN Global Ecosystem Typology 2.0 and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration—span a spectrum:

- Coasts and Mangroves

- Deserts and Semi-Deserts

- Farmlands and Mixed-Use Areas

- Forests and Woodlands

- Grasslands, Shrubs, and Savannahs

- Peatlands

- Rivers, Streams, and Lakes

- Urban Areas

Each ecosystem operates under unique conditions shaped by rainfall, temperature, soil composition, and sunlight. Forest and woodland ecosystems, for instance, thrive in moisture-rich environments, supporting dense forests. Grasslands, in contrast, endure intense wet and dry cycles, fostering limited tree growth.

Matching tree species to the appropriate ecosystem is paramount. Misaligned efforts—such as planting water-intensive trees in arid regions—can exacerbate problems rather than resolve them. Strategic planning ensures trees fulfill their role as carbon sinks while bolstering biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods.

- Indigenous Tree Species: Nature’s Resilient Allies

Indigenous tree species are the unsung heroes of reforestation efforts. These are trees that have evolved alongside their ecosystems, adapting to local soil microbes, climatic shifts, and plant competitors.

By prioritizing native species, projects not only foster natural regeneration but also minimize the need for human intervention. Indigenous trees grow without fertilizers or excessive irrigation and adapt seamlessly to seasonal environmental shifts.

Contrast this with non-native species. While fast-growing exotics like eucalyptus or pine may appear attractive, their unchecked growth can upset ecological balance. They deplete soil nutrients, compete aggressively with local flora, and, in some cases, become invasive. The preservation of ecological harmony begins with respecting what nature already knows.

- Proper Planting and Care: Cultivating Resilience

The act of planting a tree is deceptively simple, but the science of growing a forest is anything but. Success hinges on meticulous planning and execution:

- Site preparation: Clear invasive weeds and prepare soil for optimal root growth.

- Selection of quality seedlings: Avoid cheap, poorly grown options; quality ensures resilience.

- Planting techniques: Spacing and depth are critical to survival.

The work doesn’t end with planting. Seedlings demand care—consistent watering, protection from pests, and weeding. Neglect at this stage undercuts the long-term vision. A healthy forest begins with disciplined maintenance in its infancy.

- Avoiding Competition with Agriculture: A Balance of Priorities

For reforestation to succeed, it must harmonize with the needs of smallholder farmers. Land is a finite resource, and without careful planning, conflicts between agricultural pursuits and afforestation efforts can arise.

Governments and organizations must lead with inclusive policy frameworks. In Kenya, for instance, initiatives such as the Kenya Forest Policy (2014) and the National Climate Change Response Strategy provide critical guidance. These frameworks, coupled with community programs like the International Small Group and Tree Planting Program (TIST) and the Hongera Reforestation Project, empower farmers with tools for agroforestry and sustainable farming practices.

Proper zoning of land for agriculture, forestry, and wildlife corridors ensures coexistence rather than competition. Farmers trained in sustainable practices such as crop rotation and agroforestry can integrate trees into their livelihoods, multiplying the benefits of reforestation.

The Path Forward

Reforestation and afforestation are not mere acts of planting trees. They are commitments to a sustainable future, requiring thoughtful integration of ecosystems, indigenous species, technical expertise, and socio-economic considerations. As we face the unyielding threat of climate change, these efforts must be deliberate, collaborative, and backed by science. Anything less risks turning a solution into yet another environmental crisis.

The choice is ours—strategize wisely, or falter under the weight of misplaced ambition.

REFERENCES

Bas Fransen, B (2023July 22) Native VS Non-Native tree species retrieved from https://www.ecomatcher.com/native-vs-non-native-trees-all-you-need-to-know/

DGB Group (2022, January 8) 5 Types of ecosystem retrieved from; – https://www.green.earth/blog/5-types-of-ecosystems

IUCN (2022). The Restoration Barometer: a guide for governments. Gland, Switzerland

retrieved from https://iucn.org/resources/conservation-tool/restoration-barometer

Ngarize, S (2022April 7) Land-use definitions, classification systems and their correspondence to the Land categories

https://transparency-partnership.net/IPCC/LU/categories.pdf

USDA (Gov) The power of the tree retrieved from